A Look at How Torrential Rains Brought Epic Flash Floods to Maryland

Special Stories

4 Jun 2018 6:50 AM

[Mud and flood debris blanketed a section of main street below an overpass in Ellicott City, Maryland, after flash flooding. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

From NOAA by Tom Di Liberto

Less than two years after a massive flash flood destroyed large portions of the historic district of downtown Ellicott City, Maryland, even heavier rains led to a destructive repeat for the city in May 2018. While having two extreme rainfall and flooding events nearly back to back is not impossible, it certainly was improbable. Now residents are again left to pick up the pieces.

On May 27, an atmosphere laden with moisture was triggered to unleash a barrage of rain to the west of Baltimore, dropping more than six inches of rain in several hours. Rain gauges in Catonsville measured more than ten inches of rain, while Ellicott City saw around eight inches of rain.

Based on historical records, rainfall amounts this large over this short a period of time have a 0.1-0.2% chance of occurring in any given year. Or said another way, these extreme rains were a 1-in-500 to a 1-in-1000-year event.

[Cars overturned by flash flooding lean together on a sidewalk in Ellicott City, Maryland. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

Thanks to the local topography of the region, all of this water was funneled towards local tributaries and the Patapsco River. Sadly, Ellicott City is located smack dab in that funnel. And as the heavy rain poured onto pavement and other hard surfaces north of the city, it drained downhill, turning local streets into raging rivers and causing destruction along the way.

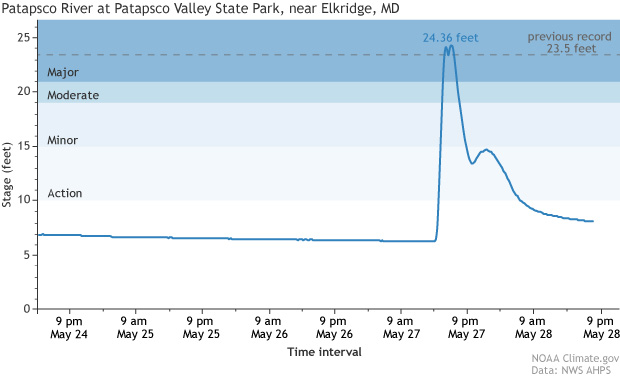

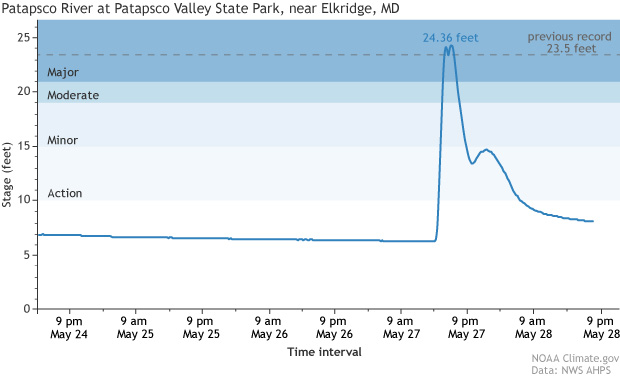

Once the water found its way to the river, water levels along the Patapsco River near Ellicott City skyrocketed. In under three hours, the river rose over 16.5 feet to a new record high of 24.36 feet. From 4:15- 5:30 p.m., the river rose nearly 3 feet every 15 minutes. The river went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour, an extremely short amount of time.

The last several days must feel like reliving a horrible nightmare for residents of Ellicott City. Two years ago in late July, a similar moisture-rich atmosphere dropped nearly half a foot of rain in just a couple of hours, leading to unbelievably damaging flash floods. At the time, that event was also called a one-in-a-thousand-year event, since statistics based on historical records estimate it had a 0.1% chance of occurring in any given year. Remarkably, less than two years later, the same area observed even more rain in another event.

[Cars overturned by flash flooding lean together on a sidewalk in Ellicott City, Maryland. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

Thanks to the local topography of the region, all of this water was funneled towards local tributaries and the Patapsco River. Sadly, Ellicott City is located smack dab in that funnel. And as the heavy rain poured onto pavement and other hard surfaces north of the city, it drained downhill, turning local streets into raging rivers and causing destruction along the way.

Once the water found its way to the river, water levels along the Patapsco River near Ellicott City skyrocketed. In under three hours, the river rose over 16.5 feet to a new record high of 24.36 feet. From 4:15- 5:30 p.m., the river rose nearly 3 feet every 15 minutes. The river went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour, an extremely short amount of time.

The last several days must feel like reliving a horrible nightmare for residents of Ellicott City. Two years ago in late July, a similar moisture-rich atmosphere dropped nearly half a foot of rain in just a couple of hours, leading to unbelievably damaging flash floods. At the time, that event was also called a one-in-a-thousand-year event, since statistics based on historical records estimate it had a 0.1% chance of occurring in any given year. Remarkably, less than two years later, the same area observed even more rain in another event.

[The Patapsco River near Ellicott City, Maryland, went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour following a thousand-year extreme rain event. NOAA Climate graph based on data from NWS Advanced Hydrological Prediction Service.]

[The Patapsco River near Ellicott City, Maryland, went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour following a thousand-year extreme rain event. NOAA Climate graph based on data from NWS Advanced Hydrological Prediction Service.]

[An aerial view of Ellicott Mills Drive at Main Street in Ellicott City on May 28. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

The National Climate Assessment issued in 2014 noted that heavy downpours are increasing across the country, but especially in the Midwest and Northeast, which, in this case, includes Maryland. In the Northeast specifically, from 1958 to 2012, there has been a 71% increase in the amount of precipitation that falls during very heavy events.

If you were paying attention earlier, you might have noticed that I said the risk of a thousand-year flood is the same every year. If water falls from the sky, it has to go somewhere. If that somewhere is not into the ground, it could instead be coursing through communities until it finds a river to empty out into, with devastating consequences. That’s why NOAA is working to help American communities identify their vulnerabilities to extreme rain events and help them build resilience to extreme weather.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[An aerial view of Ellicott Mills Drive at Main Street in Ellicott City on May 28. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

The National Climate Assessment issued in 2014 noted that heavy downpours are increasing across the country, but especially in the Midwest and Northeast, which, in this case, includes Maryland. In the Northeast specifically, from 1958 to 2012, there has been a 71% increase in the amount of precipitation that falls during very heavy events.

If you were paying attention earlier, you might have noticed that I said the risk of a thousand-year flood is the same every year. If water falls from the sky, it has to go somewhere. If that somewhere is not into the ground, it could instead be coursing through communities until it finds a river to empty out into, with devastating consequences. That’s why NOAA is working to help American communities identify their vulnerabilities to extreme rain events and help them build resilience to extreme weather.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Cars overturned by flash flooding lean together on a sidewalk in Ellicott City, Maryland. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

Thanks to the local topography of the region, all of this water was funneled towards local tributaries and the Patapsco River. Sadly, Ellicott City is located smack dab in that funnel. And as the heavy rain poured onto pavement and other hard surfaces north of the city, it drained downhill, turning local streets into raging rivers and causing destruction along the way.

Once the water found its way to the river, water levels along the Patapsco River near Ellicott City skyrocketed. In under three hours, the river rose over 16.5 feet to a new record high of 24.36 feet. From 4:15- 5:30 p.m., the river rose nearly 3 feet every 15 minutes. The river went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour, an extremely short amount of time.

The last several days must feel like reliving a horrible nightmare for residents of Ellicott City. Two years ago in late July, a similar moisture-rich atmosphere dropped nearly half a foot of rain in just a couple of hours, leading to unbelievably damaging flash floods. At the time, that event was also called a one-in-a-thousand-year event, since statistics based on historical records estimate it had a 0.1% chance of occurring in any given year. Remarkably, less than two years later, the same area observed even more rain in another event.

[Cars overturned by flash flooding lean together on a sidewalk in Ellicott City, Maryland. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

Thanks to the local topography of the region, all of this water was funneled towards local tributaries and the Patapsco River. Sadly, Ellicott City is located smack dab in that funnel. And as the heavy rain poured onto pavement and other hard surfaces north of the city, it drained downhill, turning local streets into raging rivers and causing destruction along the way.

Once the water found its way to the river, water levels along the Patapsco River near Ellicott City skyrocketed. In under three hours, the river rose over 16.5 feet to a new record high of 24.36 feet. From 4:15- 5:30 p.m., the river rose nearly 3 feet every 15 minutes. The river went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour, an extremely short amount of time.

The last several days must feel like reliving a horrible nightmare for residents of Ellicott City. Two years ago in late July, a similar moisture-rich atmosphere dropped nearly half a foot of rain in just a couple of hours, leading to unbelievably damaging flash floods. At the time, that event was also called a one-in-a-thousand-year event, since statistics based on historical records estimate it had a 0.1% chance of occurring in any given year. Remarkably, less than two years later, the same area observed even more rain in another event.

[The Patapsco River near Ellicott City, Maryland, went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour following a thousand-year extreme rain event. NOAA Climate graph based on data from NWS Advanced Hydrological Prediction Service.]

[The Patapsco River near Ellicott City, Maryland, went from normal to major flood stage in a little over an hour following a thousand-year extreme rain event. NOAA Climate graph based on data from NWS Advanced Hydrological Prediction Service.]

Don’t we have to wait a thousand years for another thousand year event?

No! But I completely understand the confusion. All a one-in-a-thousand-year event means is that at the start of any given year, there is a 1/1000 or 0.1% chance of a rainfall event of that magnitude occurring. Those numbers are true for the start of any year, so even after a thousand-year event occurred in 2016, there still was a 0.1% chance of another event of similar magnitude happening in 2017 and 2018 (and 2019, 2020, 2021… you get it). Think of it this way. The chances of winning the lottery are unbelievably low. Now imagine one day you win the lottery (somehow) but decide to keep buying lottery tickets in the future. The reason you (very, very likely) won’t win again is because winning the lottery is such an extremely rare thing, not because you have won recently. The new ticket doesn’t magically “know” your past history in the lottery. For a deeper dive, check out this article.But how do flash floods happen?

When rain falls incredibly fast over any terrain, it’s impossible for the ground to absorb all of it once. How the local terrain funnels the resulting unabsorbed water determines which areas might get damaged. In this case, a couple of factors exacerbated the flash flooding risk. A wet April in the Mid-Atlantic had led to soggy soils, limiting the amount of additional water that could be absorbed. Plus, in general, land across the United States is much more paved than it was fifty to a hundred years ago. This has turned permeable surfaces like soil into impervious ones like asphalt and concrete. When these human-factors are put together with an extreme atmospheric “factor,” like these incredibly heavy thunderstorms, the risk of disaster increases. [An aerial view of Ellicott Mills Drive at Main Street in Ellicott City on May 28. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

The National Climate Assessment issued in 2014 noted that heavy downpours are increasing across the country, but especially in the Midwest and Northeast, which, in this case, includes Maryland. In the Northeast specifically, from 1958 to 2012, there has been a 71% increase in the amount of precipitation that falls during very heavy events.

If you were paying attention earlier, you might have noticed that I said the risk of a thousand-year flood is the same every year. If water falls from the sky, it has to go somewhere. If that somewhere is not into the ground, it could instead be coursing through communities until it finds a river to empty out into, with devastating consequences. That’s why NOAA is working to help American communities identify their vulnerabilities to extreme rain events and help them build resilience to extreme weather.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[An aerial view of Ellicott Mills Drive at Main Street in Ellicott City on May 28. Photo courtesy Howard County government.]

The National Climate Assessment issued in 2014 noted that heavy downpours are increasing across the country, but especially in the Midwest and Northeast, which, in this case, includes Maryland. In the Northeast specifically, from 1958 to 2012, there has been a 71% increase in the amount of precipitation that falls during very heavy events.

If you were paying attention earlier, you might have noticed that I said the risk of a thousand-year flood is the same every year. If water falls from the sky, it has to go somewhere. If that somewhere is not into the ground, it could instead be coursing through communities until it finds a river to empty out into, with devastating consequences. That’s why NOAA is working to help American communities identify their vulnerabilities to extreme rain events and help them build resilience to extreme weather.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace MichaelsAll Weather News

More