Improving Long Term Forecasts to Predict Unusual California Precipitation

Special Stories

30 Jul 2018 9:15 AM

[San Luis Reservoir during the drought in California, February 5, 2014. Photo courtesy the California Department of Water Resources/Florence Low.]

From NOAA by Ali Stevens

Last spring, Governor Jerry Brown declared an end to California’s historic drought that caused over $5 billion in damage to agriculture as well as substantial impacts to fisheries, infrastructure, human health, and vegetation. The drought was not only severe, but it also spanned the winters of 2015-16 and 2016-17, which had unusual and unexpected precipitation that affected the drought’s evolution.

Despite surrounding ocean conditions that often support reliable seasonal forecasts through long-distance relationships with the atmosphere, predictions made a season ahead of California precipitation during these winters performed poorly. However, a new study by scientists from Columbia University, funded by the NOAA MAPP Program, shows that forecasts issued a month ahead - within the subseasonal timescale and much further ahead than a normal weather forecast - could have accurately predicted the abnormal winter rain.

To see if subseasonal forecasts could have found the “signal”, or accurate predictions, from the two unusual winters where “noise”, or uncertainty in the forecasts, interrupted the signal, Wang and his team assessed model data from the international S2S Prediction Project.

[Don Pedro Reservoir during the drought]

“Our study indicates that subseasonal to seasonal forecasts (S2S) made two weeks to two months ahead of time are highly valuable in this regard,” said Shuguang Wang, lead author of the recently pusblished paper. “This is perhaps the first study showing that S2S forecasts can accurately predict high impact weather events.”

[Don Pedro Reservoir during the drought]

“Our study indicates that subseasonal to seasonal forecasts (S2S) made two weeks to two months ahead of time are highly valuable in this regard,” said Shuguang Wang, lead author of the recently pusblished paper. “This is perhaps the first study showing that S2S forecasts can accurately predict high impact weather events.”

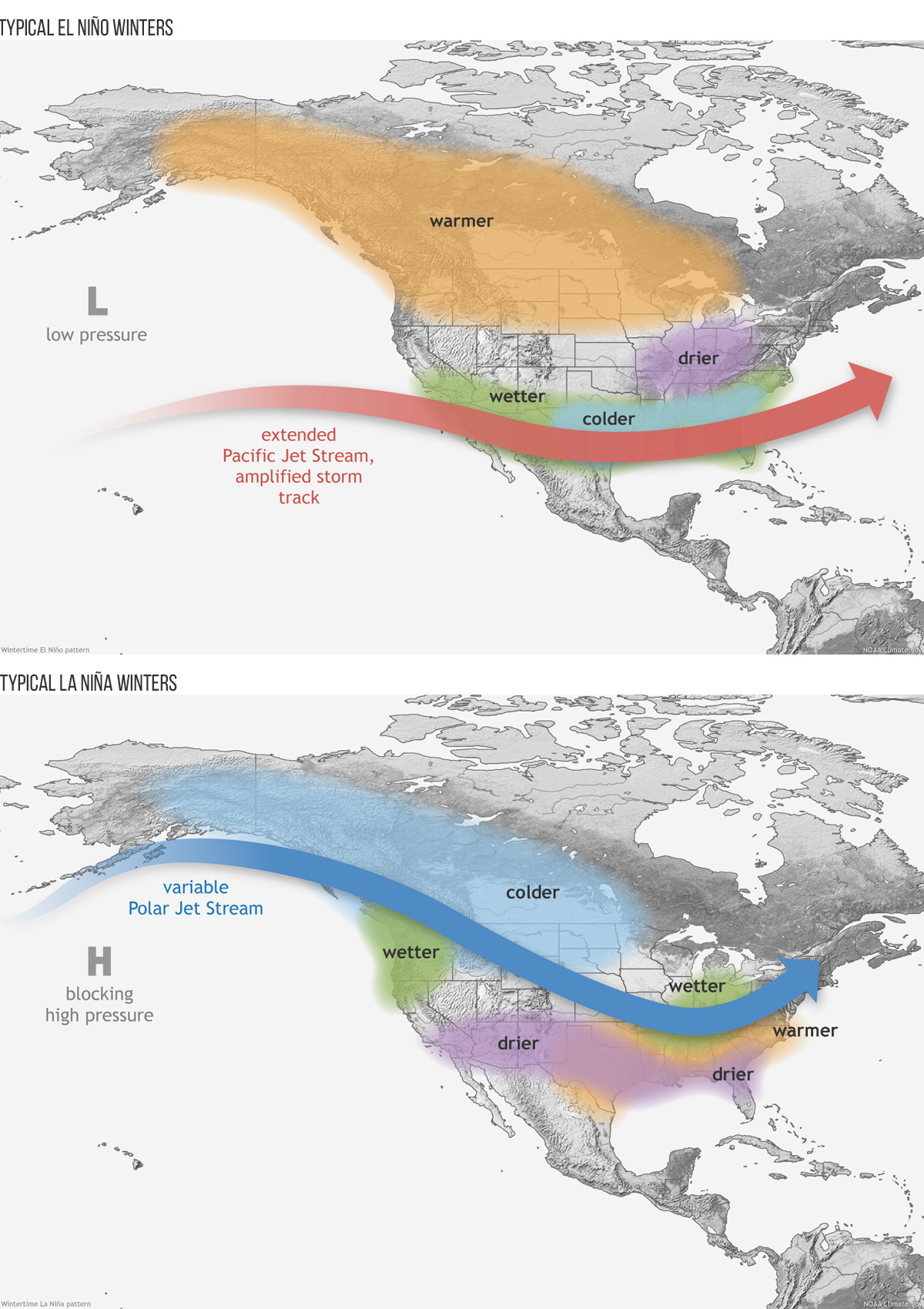

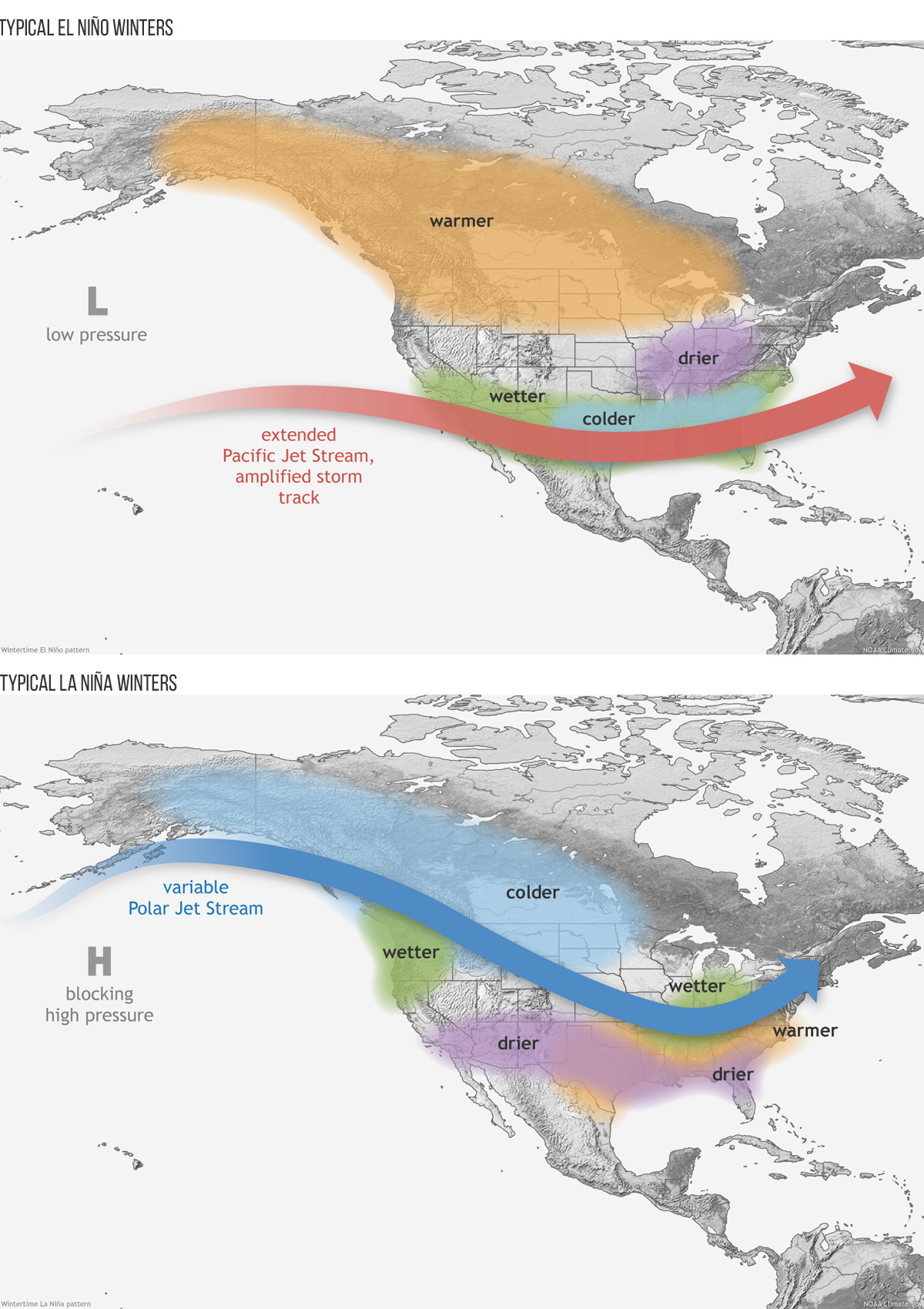

[These maps illustrate the typical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on U.S. winter weather. During La Niña, the Pacific jet stream often meanders high into the North Pacific and and is less reliable across the southern tier of the United States. The southern tier of U.S. states—from California to the Carolinas—tends to be warmer and drier than average. During El Niño, these deviations from the average are approximately (but not exactly) reversed.]

With NOAA’s recently issued El Niño Watch, Wang’s research suggests that considering subseasonal predictions this winter could help improve forecasts of potential impacts in California, and find that signal in the noise.

“As the lead time reduces from seasonal to subseasonal time scales, noise becomes signal and the forecasts change,” said Wang. This reduction in lead time results in predictions that accurately determine whether California will be drier or wetter than normal and even how dry or wet the state will be a month in advance.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[These maps illustrate the typical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on U.S. winter weather. During La Niña, the Pacific jet stream often meanders high into the North Pacific and and is less reliable across the southern tier of the United States. The southern tier of U.S. states—from California to the Carolinas—tends to be warmer and drier than average. During El Niño, these deviations from the average are approximately (but not exactly) reversed.]

With NOAA’s recently issued El Niño Watch, Wang’s research suggests that considering subseasonal predictions this winter could help improve forecasts of potential impacts in California, and find that signal in the noise.

“As the lead time reduces from seasonal to subseasonal time scales, noise becomes signal and the forecasts change,” said Wang. This reduction in lead time results in predictions that accurately determine whether California will be drier or wetter than normal and even how dry or wet the state will be a month in advance.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[Don Pedro Reservoir during the drought]

“Our study indicates that subseasonal to seasonal forecasts (S2S) made two weeks to two months ahead of time are highly valuable in this regard,” said Shuguang Wang, lead author of the recently pusblished paper. “This is perhaps the first study showing that S2S forecasts can accurately predict high impact weather events.”

[Don Pedro Reservoir during the drought]

“Our study indicates that subseasonal to seasonal forecasts (S2S) made two weeks to two months ahead of time are highly valuable in this regard,” said Shuguang Wang, lead author of the recently pusblished paper. “This is perhaps the first study showing that S2S forecasts can accurately predict high impact weather events.”

EL NIÑO, LA NIÑA AND CALIFORNIA PRECIPITATION

During the 2015-16 winter, the tropical Pacific Ocean experienced a warming event, known as El Niño, so strong that scientists nicknamed it “Godzilla”. Since El Niño events typically bring rain, forecasters and Californians eagerly expected and hoped for a barrage of storm after storm to drench the ongoing drought. Unfortunately, the storm-steering jet stream shifted north, blindsiding forecasters and robbing Californians of their very much needed rain. During the 2016-17 winter, despite a weak La Niña, or cooling event that causes drier than normal conditions, the jet stream shifted and several heavy rainfall events hit California and finally reduced the drought. This shocked forecasters and was the second wettest winter in 122 years of record. Like a crowd of muffled voices drowning out a shout, tiny changes in conditions at the time of the forecast grow and substantially change the final outcome, preventing signal from shining through the noise. This unpredictable noise dominated the California winters of 2015-16 and 2016-17, so seasonal forecasts made several months ahead of time, based on typical outcomes from El Niño or La Niña and California rain, were wrong. [These maps illustrate the typical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on U.S. winter weather. During La Niña, the Pacific jet stream often meanders high into the North Pacific and and is less reliable across the southern tier of the United States. The southern tier of U.S. states—from California to the Carolinas—tends to be warmer and drier than average. During El Niño, these deviations from the average are approximately (but not exactly) reversed.]

With NOAA’s recently issued El Niño Watch, Wang’s research suggests that considering subseasonal predictions this winter could help improve forecasts of potential impacts in California, and find that signal in the noise.

“As the lead time reduces from seasonal to subseasonal time scales, noise becomes signal and the forecasts change,” said Wang. This reduction in lead time results in predictions that accurately determine whether California will be drier or wetter than normal and even how dry or wet the state will be a month in advance.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

[These maps illustrate the typical impacts of El Niño and La Niña on U.S. winter weather. During La Niña, the Pacific jet stream often meanders high into the North Pacific and and is less reliable across the southern tier of the United States. The southern tier of U.S. states—from California to the Carolinas—tends to be warmer and drier than average. During El Niño, these deviations from the average are approximately (but not exactly) reversed.]

With NOAA’s recently issued El Niño Watch, Wang’s research suggests that considering subseasonal predictions this winter could help improve forecasts of potential impacts in California, and find that signal in the noise.

“As the lead time reduces from seasonal to subseasonal time scales, noise becomes signal and the forecasts change,” said Wang. This reduction in lead time results in predictions that accurately determine whether California will be drier or wetter than normal and even how dry or wet the state will be a month in advance.

Edited for WeatherNation by Meteorologist Mace Michaels

All Weather News

More